Would Ratifying ILO’s C189 and C190 Pave the Way for a Progressive Care Economy in Africa?

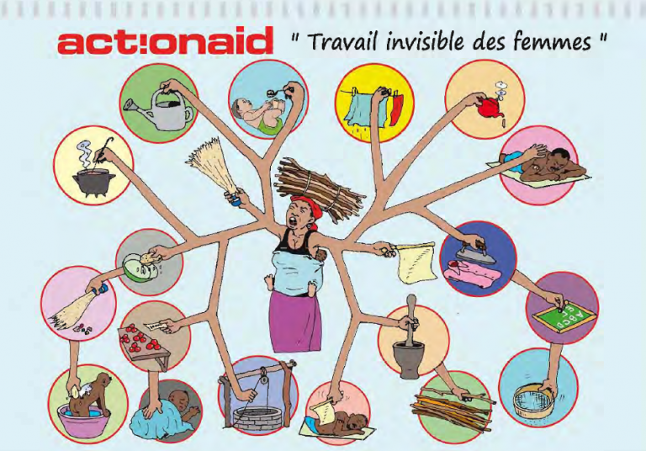

An African woman’s alarm clock isn’t always a rooster. Often, it is the relentless tick-tock of unpaid care work. She shoulders a burden that millions of African women and girls all know too well: fetching water, cooking, laundry, cleaning, childcare or eldercare, grocery shopping and long treks to tend to her household – an invisible marathon that stretches from dusk to dawn, and on a daily basis! The reward? Exhaustion, limited participation in the workforce, no recognition, meager compensation and little to no support.

Here’s the crux of the matter: The current system of unpaid care work is crippling, not just for women and girls who shoulder its immense burden, but also for Africa’s economic and social development. Could ratifying the International Labor Organization’s (ILO) Conventions 189 and 190 usher in a progressive care economy for Africa?

A Glimpse into the Current Status Quo

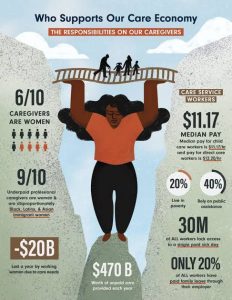

Care work – the ever-present yet invisible thread woven through every day – takes on a monumental role in our lives. Still, it often goes unnoticed and remains unappreciated. The ILO sheds light on the staggering reality: women and girls globally perform more than three-quarters of unpaid care work, amounting to a mind-blowing 16.4 billion hours daily.

Globally, it is estimated that the monetary value of women’s unpaid care work globally is a mind-blowing US $10.8 trillion annually – an amount that is three times the size of the world’s tech industry. Studies suggest that if valued monetarily, unpaid care work in Africa could represent a substantial portion of GDP, exceeding 40% in some countries.

It is thus no surprise that a stark 42 per cent of women across the globe cannot get decent jobs because they are responsible for all the caregiving, compared to a mere 6 percent of men. Here’s where the impact on Africa becomes even more evident.

The statistics paint a clear picture: care work is Africa’s invisible economic powerhouse. Hence, there is an immediate need to use the potential of our young and working-age potential to create more wealth for everyone.

The Promise of ILO Conventions 189 and 190

As stakeholders across the globe pursue active discourse on reimagining a care economy that works for all, governments ratifying the ILO conventions would signify a commitment to creating a fairer and more just care ecosystem in Africa.

Adopted globally in 2019, the ILO’s Decent Work for Domestic Workers Convention (C189) grants domestic workers basic labor rights like minimum wage, limitations on working hours, and social security. The Violence and Harassment Convention (C190) on the other hand, tackles the pervasive issue of violence and harassment faced by many care workers, creating a safer and more dignified work environment.

In these conventions, lie the 5Rs of building a progressive care economy, which include: Recognition (Acknowledging the social and economic value of care work – both paid and unpaid); Reduction (Investing in Policies and investments to reduce the burden of unpaid care, particularly on women, and promote gender equality and workforce participation); Redistribution (Sharing the responsibility for care between families, communities and the state is necessary to ensure equitable access to care services); Rewarding (Upgrading the pay and working conditions of care workers through minimum wage regulations and social security benefits enhances their dignity and professionalism); and Representation (Empowering care workers through strong unions and worker organizations is vital for ensuring their voices are heard and their rights are protected).

The Ratification Race: A Game Changer for Africa’s Care Economy?

The quest for a progressive, just and sustainable care economy is gaining momentum! As of 2024, 37 countries worldwide have ratified the convention (C189) and 39 have ratified ILO C190. While the scoreboard needs more entries, these numbers represent a testament to the growing commitment to safeguarding the lives of African women and girls, as well as care workers in general. The Nordic Countries (Norway, Sweden, Finland, Denmark, and Iceland) offer a compelling case study for the potential benefits of ratifying these conventions. As highlighted in several international assessments, their progressive care infrastructure remains a key factor in their success.

Africa’s journey towards a fairer care economy, on the other hand, has seen progress amidst several challenges, with several African countries taking a bold step to ratify the ILO conventions and streamline their national labor frameworks. Mauritius (C189 in 2012 and C190 in 2018), for instance, boasts a relatively well-developed social security system and a minimum wage applicable to domestic workers. However, potential exploitation of migrant workers and enforcement gaps remain hurdles to overcome. Similarly, South Africa’s (C189 was ratified in 2013 and C190 in 2018) landscape for care work is characterized by a strong legal framework for worker protection, but the country still grapples with high unemployment rates and a vast informal care economy, hindering the extension of social benefits such as minimum wage and healthcare access, among several others.

Tunisia, on the other hand, whose government ratified C189 in 2011 and C190 in 2019 has seen significant reforms in recent years, including a national domestic worker law. However, implementation and enforcement remain concerns, and the care economy is still largely informal. In Cabo Verde (where C189 was ratified in and C190 in), Namibia and Ghana, legal labor frameworks have been established to support the cause. Still, these countries face a number of enforcement challenges.

Kenya’s recent public participation exercise geared towards the adoption and implementation of ILO’s C189 and C190 through its Ministry of Labor and Social Protection demonstrates a commitment to improving working conditions for domestic and care workers. Uganda, has also not been left behind as it seeks to join the ratification journey to a just care economy in August 2024.

It is worth noting that Rwanda, without ratifying the conventions, established a social security scheme in 2010 with the potential to include domestic workers. Similarly, Ethiopia has a social security scheme with potential future inclusion of domestic workers, but hasn’t ratified the conventions yet. Both countries, alongside others, are considering ratification, but concerns exist. Critics argue that ratification entails bureaucratic processes and costs that could overshadow pressing development priorities. Some advocate for focusing on implementation of existing policies rather than symbolic gestures. However, we can no longer ignore the fact that a robust care infrastructure in Africa has long-term economic and social benefits, including increased female workforce participation and national GDP growth.

Furthermore, ratification offers more than a symbolic gesture. It creates a legal obligation to uphold the conventions and promote worker rights, which in turn attracts the requisite international scrutiny that pushes for maintaining or improving labor standards in any given country. It is also a golden opportunity to strengthen domestic laws, as well as care regulations and institutions. Finally, ratification increases a country’s visibility within the ILO framework, potentially leading to access to resources and technical support.

Building a Just Care Economy: A Pan-African Feminist Perspective

The fight for a progressive care economy in Africa is deeply intertwined with the struggles for gender equality and social justice. As such, a Pan-African Feminist Perspective recognizes that ratifying ILO Conventions 189 and 190 is not a one-size-fits-all solution but is a critical first step to a progressive care economy in the continent. True transformation requires a clear understanding of Africa’s unique context and a deeper dive into the historical, cultural and socio-economic realities that have placed a disproportionate burden of care on women and girls. There is a need for continuous focus on social dialogue and education campaigns are crucial to promote gender equality and raise awareness about worker rights, as well as encourage a more equitable distribution of caregiving responsibilities between men and women.

Moreover, a robust socialized public sector response is essential to necessitate a paradigm shift to care work in Africa. This could involve initiatives like government-funded childcare centers, eldercare facilities, and subsidized home care services. Such measures can free up women’s time for paid employment and promote gender equality. Lastly, discourse and decision-making by African governments and policy makers on the care economy must prioritize the lived experiences of African women and girls. Policies need to be crafted with their specific needs and challenges in mind. This can be achieved through consultations with women’s organizations, incorporating their perspectives into policy design and implementation.

In essence, combining legal frameworks with social change, investment in care infrastructure, and a focus on women’s empowerment, paves the way for Africa to build a transformative care economy that values its workforce and ensures a just future for all.

This blog was written by Lurit Yugusuk and peer reviewed by Grace Namugambe, who both work in FEMNET’s EJR Programme. For more details about the blog, reach out to Lurit Yugusuk via l.yugusuk@femnet.or.ke

Related Posts

Establishing a Revolutionary Era of Resistance: A Feminist Perspective on Kenya’s Finance Bill 2024

On June 20, 2024, citizens of Kenya from all regions of the country participated in a second round

Learn MoreVoices For Equality – An Advocacy Guide To Fiscal Justice For Women and Girls in Africa

The language of fiscal policy might often feel like navigating a highway of technical jargon. However, beneath the

Learn More