Establishing a Revolutionary Era of Resistance: A Feminist Perspective on Kenya’s Finance Bill 2024

On June 20, 2024, citizens of Kenya from all regions of the country participated in a second round of public demonstrations to express their opposition to the Finance Bill of 2024. An assertive and daring stance to call for the rejection of the Finance Bill. A large majority, primarily consisting of Gen Zs, (born between 1997 and 2012), is seeing a gradual increase in political influence as they become progressively more vocal about their rights.

These youth united to hold their leaders accountable for the promises they made during their campaign for votes in 2022. However, the leaders disregarded Kenyans’ pleas and passed the bill. 204 members of parliament voted in favour of a tool that they believe will help reduce Kenya’s high debt burdens, improve public services like education and healthcare, and promote overall economic growth. However, I view this bill as a form of economic violence, particularly against women and girls in Kenya, due to its superficiality, discriminatory nature, lack of consideration for gender issues, and potential to worsen poverty levels.

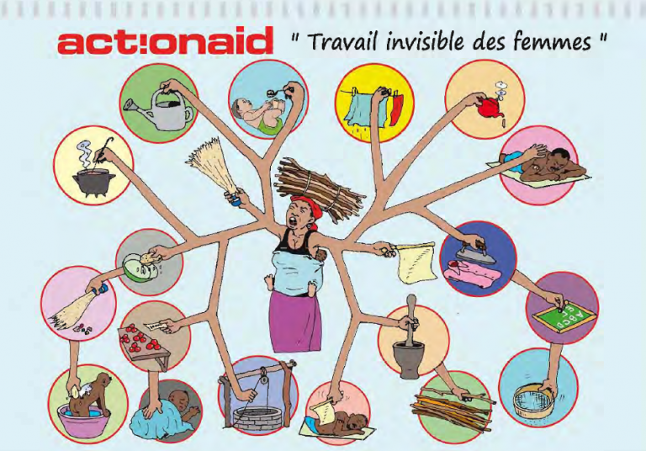

According to Global Financial Integrity (GFI), Kenya loses billions of shillings yearly due to illicit financial flows (IFFs) caused by corruption, trade mis-invoicing, money laundering, and tax evasion. Consequently, Kenya was placed on the grey list by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) on February 23, 2024, causing significant concern within the economic sector. However, rather than members of parliament convening to tackle reducing these IFFs hindering Kenya’s progress, all attention was given to setting up more regressive tax policies that will primarily impact vulnerable individuals. These include women and girls living in poverty and marginalised women in all their diversity who heavily depend on public services. When the existing public services are inaccessible and insufficient, women, girls, and marginalised communities are responsible for providing the services by performing tasks that the government should provide. Women have a larger burden of caregiving responsibilities for families and homes, most of which is unpaid labour. The imposition of a consumption tax on essential goods further exacerbates the already dire circumstances faced by unpaid carers, particularly those who care for families who can barely make ends meet, impacting the most economically disadvantaged families, including rural women and women living in informal urban settlements.

While locally produced sanitary pads and diapers are not subject to the Eco Levy, women and girls who depend on imported sanitary towels and diapers are nevertheless affected. Not long ago, Scheaffre Okore’s article on several Kenyan women on their #MyAlwaysExperience shed light on why Kenyan women and girls prefer imported sanitary towels. Kenyan women spoke out about the distressing and uncomfortable effects they have had from using locally manufactured Always pads. These effects have been severe enough to cause trauma or require ongoing medical treatment for various symptoms. Eliminating the eco levy on sanitary towels and diapers made in our country does not provide a solution; rather, it contributes to the growing occurrence of women’s health issues, as seen above. Particularly if you are encouraging us to buy locally made products by lowering taxes on them and increasing taxes on globally produced items. Another aspect that requires attention is the local production costs. Eliminating tariffs on raw materials, providing growth-supportive corporate tax rates, and granting access to financial resources and loans for local producers may stimulate local manufacturing and foster stronger competitiveness with internationally manufactured products. Such considerations will benefit both the local producer and the user. It is crucial to consider company interests during tax removal talks to safeguard market competitiveness and preserve the quality of these essential products. Kenyan women and girls need high-quality finished products manufactured with premium materials and cotton that meet approved production standards. These products should be available at a subsidised cost or, ideally, provided for free. This way, all women and girls, including those in marginalised counties, can easily access sanitary towels.

The transition to the Social Health Insurance Fund (SHIF) from the National Health Insurance Fund (NHIF) is seen as Kenya’s new era of healthcare funding, requiring Kenyans to contribute 2.75% of their total monthly income. The shift, while intended to tackle current gaps in healthcare, calls for meticulous execution to guarantee its triumph. Corruption within the health sector, which encompasses embezzlement of funds and manipulation of procurement processes, has significant ramifications for both the accessibility and quality of healthcare. The absence of openness in procurement renders public health expenditure susceptible to corruption, a concern voiced by many Kenyans. The question is whether they have gained knowledge from the lessons of NHIF or if this is simply another scandal marinating. On the promise of one facility for every 5000 citizens, will these facilities provide free maternal healthcare? Will they offer complimentary, secure, and easily reachable family planning amenities? Will the healthcare workers in these facilities be provided with sufficient medical supplies regularly, not overworked and underpaid and have access to social protection mechanisms/benefits and pensions? Will the new SHIF system implement a gender quota system encompassing all levels, including procurement processes and employment possibilities, to address the gender pay gap in the health sector and encourage more girls to pursue careers in public healthcare? Will the SHIF programme also encompass violence recovery services, including mental health support, specifically tailored for women and girls? These few unanswered questions have left many Kenyans concerned that their hard-earned money may not reach them or those who need it the most.

Women in Kenya experience substantial prejudice in the ownership and access to land due to the deeply rooted patriarchal structure that still exists today in several areas. Kenya Land Alliance reported that women own a mere 1% of all land titles in their individual names and 5-6 %when held jointly. Although there have been significant advancements in recent years, data indicates a decrease in women’s land ownership. According to KIPPRA, In 2022, the percentage of land ownership among women decreased to 75.0% for agricultural property and 93.3% for non-agricultural land. Section 51 of the finance bill introduces a new provision to the Land Act stating that owners of freehold land located within urban areas or cities must pay an annual land levy. This levy will be equivalent to the rent charged for a leasehold land or property of the same size in the same zone. Although owners of freehold property used for agriculture may be excluded from the annual land tax, this exemption disproportionately affects women, who constitute 80% of the agricultural workforce and play a significant role in the economic revenue of the agricultural sector in Kenya.

Kenyan women have faced significant challenges in acquiring and making use of land. These challenges may be ascribed to discriminatory customary regulations and practices, as well as criteria such as marital status and age amongst other factors. The Constitution of Kenya 2010 explicitly outlines four fundamental land rights, including eradicating gender bias in traditions, laws, and practices concerning land and property; the assurance of land rights security and fair and equal access to land, etc. The proposal to introduce a land tax on freehold land will increase the complexity of land ownership for all, especially women, and make it more challenging to retain ownership due to the requirement of paying annual land levies. Failure to comply with these levies would result in the government repossessing the land. This will significantly reverse any progress achieved in women’s land rights. Kenya is now experiencing a significant gap between the small agricultural land women hold and the large proportion of women working in agriculture. Additionally, there are urgent concerns about the impact of neoliberal economic policies, which disproportionately affect women. Hence, the government must confront the overlapping manifestations of discrimination experienced by Kenyan women and girls in relation to land ownership in accordance with their legal commitments, which is crucial to advancing women’s land rights and equality and achieving Sustainable Development Goal 5 on gender equality.

“Economic violence is when the abuser has complete control over the victim’s money and other economic resources or activities.” (Fawole 2008). The 204 members of parliament who voted for the bill may be characterised as perpetrators of economic violence. They intend to retain authority over the financial welfare of Kenyans, disregarding our input and dictating how the money should be allocated. Consequently, this diminishes the autonomy of Kenyans, rendering us entirely reliant on ourselves for the very things that are our rights per the Kenyan constitution, the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights and Universal human rights law. For women and girls, the shoe pinches more, from sanitary towels to essential items such as food products, fuel, petrol, and charcoal. The expenses related to maternity healthcare continue to rise every quarter, and most recently, there have been instances where mothers have had to travel long distances to access vaccines and immunizations for their newborns and infants. During times of economic crises, women’s bodies are often disproportionately affected by the negative consequences of capitalism. Political and socioeconomic struggles can be considered feminist because they involve a critical analysis of how capitalism destroys resources essential for the survival and reproduction of societies.

As the world commemorates the 30th anniversary of the Beijing Declaration on women’s rights next year, the progress achieved in Kenya since 1995 is at risk of being undermined by the consequences of the finance bill. To safeguard women’s rights and prevent any regression in achieving SDG 5, the Kenyan government must consider and ban the economic aggression embedded in the present finance bill. And to the women who came out from all corners of the country to protest through various methods of activism, thank you! You continue to contribute to and influence the Kenyan revolution by consistently displaying courage in your authenticity. Millie Odhiambo, one of our prominent feminist leaders in parliament, has been a vocal advocate for daring to be bold and disregarding cultural expectations that limit the visibility and voice of women. She encourages us to embrace who we are and not shy away from expressing our truths, even if it means defying societal norms and being perceived as “bad girls”.

Kenyan women, including young women like Shakira Wafula, who epitomised bravery and courage, have been at the forefront of protests on the various streets of Kenya. Our acts of resistance persistently feature in various media headlines, as seen when we collectively mobilised to protest the escalating incidents of femicide at ‘Feminists March Against Femicide‘.Women’s solidarity in resistance is like a dormant volcano becoming active. It is time to erupt and dismantle the very economic systems and structures that have oppressed us for generations. A comprehensive evaluation and analysis of the entire system is necessary. The resistance to capitalism is not solely shaped by the structure of capitalist accumulation and governance but rather by the lived experiences of women, which influence their methods of resistance(Ossome 2021). Addressing poverty reduction, enhancing national healthcare, and guaranteeing access to clean water, food sovereignty, housing, and energy supply and distribution—universally cherished rights—are imperative. These factors would significantly enhance the empowerment of Kenyan women and girls who experience a disproportionate lack of access to these rights.

Authored by: Nicole Maloba is a lawyer and policy researcher dedicated to closing the gap between localised efforts to promote women’s socioeconomic rights and broader endeavours to reshape economies through legislative gender reform and feminist macroeconomics analysis. She is the Economic Justice and Rights Lead at FEMNET

Related Tags

Related Posts

Voices For Equality – An Advocacy Guide To Fiscal Justice For Women and Girls in Africa

The language of fiscal policy might often feel like navigating a highway of technical jargon. However, beneath the

Learn MoreWould Ratifying ILO’s C189 and C190 Pave the Way for a Progressive Care Economy in Africa?

An African woman’s alarm clock isn’t always a rooster. Often, it is the relentless tick-tock of unpaid care

Learn More